History of Inflation Part IV – The Final Collapse and the First Paper Money

If you’ve been following our series, you know that the state of Polish currency has been deteriorating over the years. However, we have now reached a critical moment. After the death of Jan III Sobieski, the throne was occupied by the Wettin dynasty. And things started to take a turn for the worse…

History of Inflation in Poland – from Mieszko I to Kazimierz the Great

History of Inflation in Poland Part II – The Jagiellonian Dynasty

History of Inflation in Poland Part III – XV-XVII Century, Neighbor is a Wolf to Neighbor

The King Who Harmed His Own Country

Augustus II the Strong is remembered in our history as a great partygoer, a friend of Tsar Peter the Great, and also the father of a record number of illegitimate children. Unfortunately, he was also notorious for debasing the Polish currency. Although the pacta conventa forbade the king from minting coins independently, Augustus paid little attention to that. He established mints in Leipzig, Dresden, and Guben, where silver and copper coins were minted. This had unfortunate consequences for Poland. It could be said that both Augustus II and his son, Augustus III, cared more about the interests of their native Saxony than those of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Poland was flooded with copper coins, while Polish silver coins were exported to the homelands of both rulers. Allegedly, Augustus III’s annual income from this practice amounted to as much as 680,000 Polish złotys. Over the years, our country was inundated with low-quality coins with a total value of 600 million złotys. To illustrate the impact, imagine that many transactions were conducted using bags of money, and larger sums were transported by horse-drawn wagons.

As if an internal enemy was not enough, Frederick II, the ruler of Prussia, also contributed to the problem. When he occupied Leipzig in 1756, he took over Augustus III’s mint along with his dies. The consequences were not long in coming. Our neighbors once again began flooding us with poor-quality currency. Allegedly, within 7 years, Prussia made a profit of 25 million thalers from this.

Stanisław August Poniatowski and the First Financial Crash

Stanisław August Poniatowski, who ascended the Polish throne after Augustus III, attempted to address the situation. In 1764, he took full control of the money issuance from the Sejm and two years later, established two mints – one for copper in Kraków and one for silver in Warsaw. He also ordered the withdrawal of foreign coins from circulation and their re-minting into domestic units. However, it must be honestly admitted that his ideas had little chance of implementation, as the country was already in a period of decline.

Moreover, it turned out that under his reign, we experienced as a nation the first banking crash! And that, ironically, occurred before the establishment of a central bank. How did it happen?

During this time, Europe was already on the brink of the Industrial Revolution. Banks were emerging more and more, and this process was also taking place in Poland. Leading bankers included Prot Potocki and Piotr Tepper, among others. Naturally, they believed that money had to be in constant circulation, so they frequently borrowed the deposited funds. Potocki himself lent the state 100,000 złotys.

Business was thriving, but only for a while. Suddenly, the liquidity of banks started to collapse, and Polish bankers had to seek loans abroad. Unfortunately, they began to face refusals there as well. Then everything began to collapse like dominoes.

In January 1793, Prussian forces entered Greater Poland, causing immense panic among the residents who rushed to the banks to withdraw their money, which was no longer sufficient for all depositors. Eventually, on February 25, 1793, Tepper became the first banker to declare bankruptcy.

Subsequently, more banks started to fall. This crash deprived many citizens of the Commonwealth of their savings and coincided with the Second Partition of the country.

Enter Paper Money

But that’s not all. When everything is going in the wrong direction, there is always a hero who tries to bring rescue. This hero was Tadeusz Kościuszko. However, to save the world, one needs… yes, money.

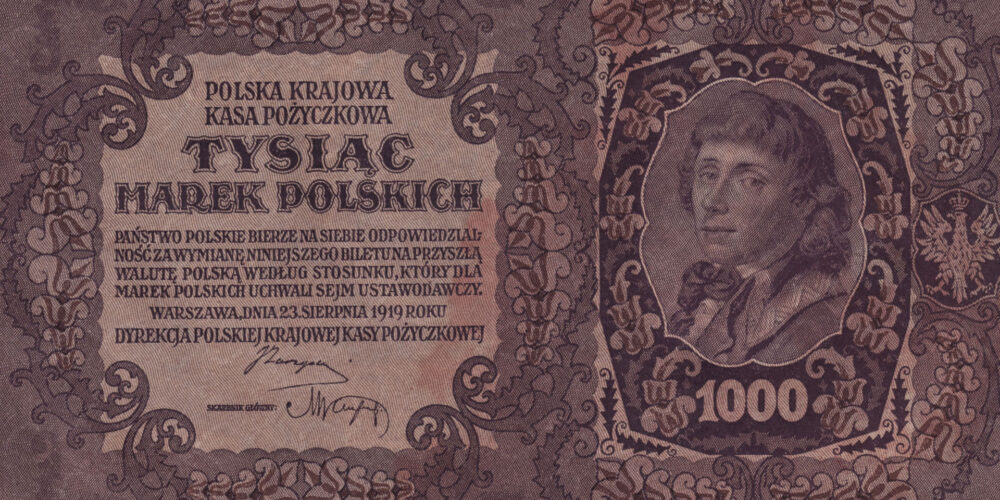

However, it was still difficult to mint coins due to a lack of metal. Although it was possible to confiscate all the metal from churches and monasteries (even melting down figurines of apostles from the Mariacki Church), it was still not enough. On June 8, 1794, the National Supreme Council issued paper money equivalent to 60 million złotys. The issuance was backed by national assets. However, there was one condition for redeeming the notes (or banknotes of that time)… the victory of Kościuszko’s uprising.

Thus, they encountered a few complications. There was a psychological aspect because for many people, paper money was not considered reliable at all (just as today, many have doubts about digital currencies). Moreover, the public’s belief in the success of the struggle against the occupiers was diminishing. As a result, prices of goods were quoted in both coins and banknotes.

As we know from history lessons, the uprising eventually failed, and the banknotes became worthless pieces of paper. In 1795, Poland disappeared from the map of Europe. For several decades, old coins continued to circulate. The period of the Napoleonic Wars was approaching, which was also to mark an interesting episode in the history of money in our lands.