History of Economic Crises. Part 7. Crisis of the Second Half of the 18th Century.

Today, we will focus on the crisis that affected several countries in Europe during the 2nd half of the 18th century.

The Crisis of 1763

The crisis that began in 1763 mainly affected the Netherlands, Prussia, and Scandinavia, but it also reached Great Britain. Some historians attribute its origins to land speculation in America, although not all economists agree on whether this is true.

Let us look for the origins of the problems where most researchers do. Firstly, it is related to the Seven Years’ War.

This mentioned conflict could be considered a prologue to the world wars. The battles took place not only in Europe but also in the colonies in the Americas.

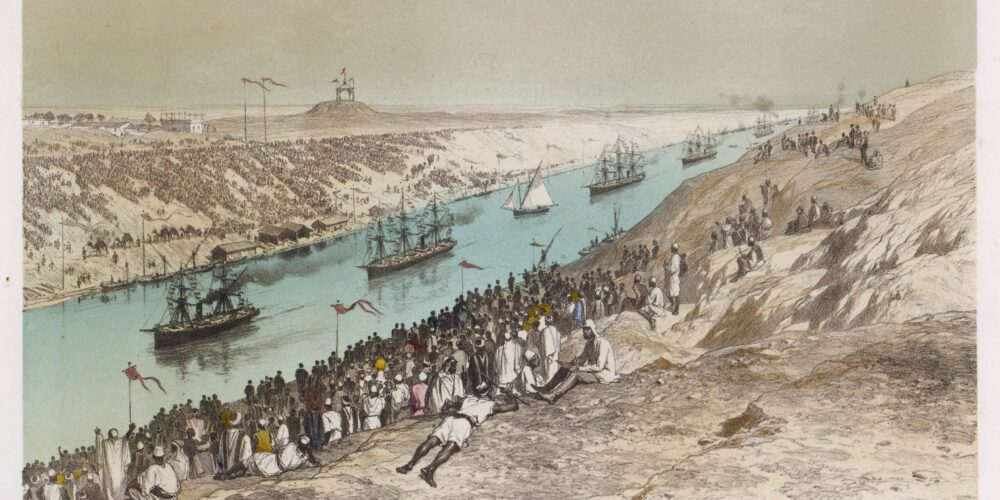

As a result of the war, Great Britain confirmed its status as a major power, pushing France, its defeated opponent, into a corner. Paris lost, among other things, colonies in India and permanently lost its influence in America. Napoleon later sealed the deal by selling Louisiana.

The war also strengthened Prussia, which indirectly contributed to the downfall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth three decades later.

Now let’s delve into the field of economics. Armed conflicts often lead to a country’s indebtedness. Amsterdam, in this case, was the place on the map where the funds were gathered to be later used to pay off the debts to British allies.

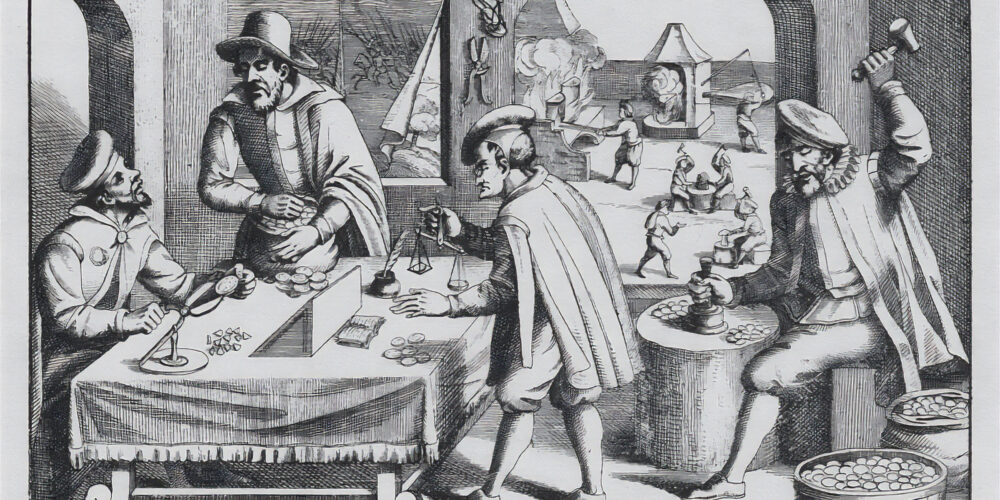

However, the Dutch engaged in a kind of credit expansion by investing in English public securities and so-called bills of exchange chains. The latter system appealed to the DeNeufville brothers, who created a credit network based on it.

How did the brothers’ system work in practice? They issued the mentioned bills of exchange on merchant houses in Stockholm, Bremen, Hamburg, Lübeck, Copenhagen, and even St. Petersburg. They thus created a credit structure, but – and this is worth emphasizing – without using a large amount of cash. We are talking about a system – as we would say today – virtual. There were also insurance bills for goods loaded on merchant ships in circulation, which were also subject to speculation. Trade flourished during the war. However, every conflict eventually comes to an end.

The System Collapses

When the war with France ended, the prices of the bills’ commercial goods fell sharply. This especially affected the sugar market. After the fighting ceased, deliveries from French West Indies were resumed, resulting in an increase in the supply of sugar on the market.

The issuers of overvalued and simply expensive bills began to lack the means to repay them. Hamburg even sent letters to Amsterdam’s merchant houses, appealing to them to suspend payments until the DeNeufville brothers resolved their financial problems as the main issuers of the bills. However, the letter reached the recipients too late. The family of financiers repaid creditors until 1799, but they still couldn’t recover most of the money.

The problem was finally resolved when King Frederick II of Prussia decided to issue new coins in Amsterdam (previously, during the war, he had devalued his silver currency). The new units were minted based on credits granted by Dutch bankers. This led to a deflation of the credit market.

London benefited from the crisis. It took over a significant portion of Dutch trade and transactions with Russia and Scandinavia.

But why do we say that the crisis was pan-European? It disrupted continental trade. Bills issued by Berlin or Swedish merchants were also protested in Amsterdam. Thus, the entire financial system of capital circulation collapsed, leading to company failures and bankruptcies of merchants.

The crisis also spread to Great Britain (through the panicked sale of English securities by Amsterdam) and to Russia and Sweden. In the case of the latter countries, the problem was the French Revolution, which caused a rapid outflow of precious metal money from France, flooding the mentioned economies.

However, the problems did not end there. The 19th century proved even more painful in this regard.

To be continued.